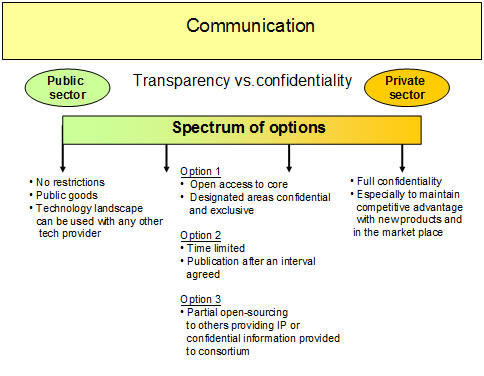

Communication and confidentiality

» Privacy

» Disclosure

» Motivation

» Knowledge management

» Information integrity

» Best practices for contract formation

- The private sector maintains a culture of privacy in research and development in order to be first to the patent office and/or gain all the advantages of leading into a new market. Private sector parties usually aim to retain privileged access to their information that has been expensive to generate. They also want to prevent its use by competitors.

- Ground-breaking science and the push for project funding in universities and public sector organizations can also be highly competitive. University spin-off companies usually also seek to retain confidentiality.

Best practice for contract formation

- Realism. The ideal scenario of open access to all information and no confidentiality constraints is unrealistic. This is especially true in PPPs with high innovation aspirations, as intellectual property will almost certainly be an issue. The Syngenta Foundation encourages all parties to keep an open mind on intellectual property and to explore new ways to resolve obstacles.

- Transparency. Confidentiality and exclusivity are often major drivers. It is therefore unrealistic to expect partners to be fully transparent and disclose all key information and obligations from Day 1. Transparency usually grows as partners identify the PPP’s full benefits and increase their mutual trust. It is essential to highlight material conflicts of interests or operational difficulties very early. This prevents investment of too much expense and time before solutions are found, or in some cases before problems prove too large for a successful PPP.

- Communications strategy. PPP business plans need to include a communications strategy and a plan covering all publicity requirements, with particular emphasis on external communications.

- Communications tactics. An annual rolling plan for jointly owned external communications is advisable. This should contain agreed milestones. If an individual party “goes public” without the others’ approval, this can seriously damage relations within the PPP. Rebuilding trust can be very difficult.

- Publication approvals process. All external communications require the parties’ joint agreement. Drafts need to be prepared early enough to allow organizations to complete their internal approval processes, which can be very time-consuming. The PPP’s “governance body” should also formally review announcements for alignment with the business plan.

- Risk management. All parties should analyze the risks and difficulties associated with communication and confidentiality. They can then take the necessary steps to overcome any problems.

- Practical operations. Partners need to consider practical measures to ensure that scientists or other collaborators are not forced into conflicts of interest. For example, if an institution already has a partnership with a company’s competitor, it is unrealistic to expect a rival set of lab or field studies to run in parallel. This would raise the risk of breach of confidentiality, and put unnecessary stress on the scientists involved. Dedicating separate principle investigators or keeping the scientific teams apart (ideally on different sites) reduces the risks.

- Publication enablers. A number of approaches can help with contract creation, either singly or in combination. They include:

1. Limited scope confidentiality

Aspects of technology, materials, processes and know-how are identified as the preserve of the PPP and form a core of confidential information covered in the contract. Other aspects can be designated as outside the contract.

2. Time-limited confidentiality

This can refer to the aspects in 1, but is more open because the confidentiality ends at an agreed time. A researcher can therefore publish a thesis or publicity needed for another project by a specific date. Time-limited confidentiality enables non-disclosure before patents are filed or intellectual property is granted. This approach is suitable where the competitive advantage or threat declines over time.

3. Consortium or nominated access

This option limits the breadth of use of the confidential information identified in 1, and restricts access (e.g. only by PPP / consortium participants or members of a patent commons). With highly sensitive information, contracts can limit access to named individuals or departments.