Intellectual Property (IP)

Facts and myths

Approaches to IP management

- IP licenses

- Patent commons

- Open source

Best practice and options to consider

- IP policy and strategy

- New innovation models

- Freedom to operate

- Transparency

- Ownership

- Inventorship

- Benefit-sharing

- IP costs and management

- Patent filing

- International legislation

PPP creation support

Intellectual Property

- Intellectual property (IP) is an essential legal instrument that is used by modern technology-based businesses, including agribusinesses, to fuel a stream of innovative products from research and development.

- IP mechanisms to protect agricultural innovations include: patents, plant variety protection (also known as PVP and plant breeders’ rights), trademarks, geographic marks that indicate country or region of origin, and trade secrets. This paper refers mainly to the use of patents and plant variety protection1. Although different mechanisms, they can be supplementary to each other to protect innovations. Both typically last for about 20 years.

1 Kock, M (2009) Patents for Life: the role of intellectual property rights on plant innovations. Bioscience Law Review, vol 10 issue 5. p.1-10

Comparison of characteristics of PVP and patent protection

| Plant Variety Protection 2 | Patents 3 | |

| Innovation protection | New plant varieties that are distinct, uniform and stable | New inventions such as. genes, traits, agrochemicals, breeding or chemical production processes |

| Applicability | Traditional and experience-based breeding | Transgenic modification e.g. pest-resistant traits, complex traits, marker-assisted breeding, new breeding processes, new agrochemical active ingredients, formulations, and manufacturing processes. |

| Exemptions and permissions | Breeders’ exemption Farmer saved seed provision | Research on inventions is allowed in many countries but a license for development and/or commercial use is required. |

2 PVP is suitable for new varieties created using traditional breeding approaches where the cultivar is recognizably visually different from other varieties, shows all these same phenotypic characteristics and breeds true year to year. Varieties can be used for further breeding providing they are legally accessed. In most countries there are no or limited restrictions on farmers saving seed to grow their next crop, nor are there payments due to the original breeder. Private or non-commercial acts are outside the scope of PVP.

3 Patents provide protection for inventions where varieties or germplasm are phenotypically indistinguishable but contain significant novel beneficial traits that have required substantial discovery research investment.

- Intellectual property rights are granted in accordance with national laws in individual countries around the world. Applications for multiple counties can be coordinated globally and regionally. For example:

- The International Patent Cooperation Treaty makes it possible to file a common patent application which can be converted at a later stage into national patent applications in a number of countries (currently 139).

- The International Union for the Protection of New Varieties in Plants (UPOV) has 68 members, many of which are developing countries.

- The African Regional Intellectual Property Organization processes patent applications for member countries in southern and eastern Africa.

- The International Patent Cooperation Treaty makes it possible to file a common patent application which can be converted at a later stage into national patent applications in a number of countries (currently 139).

Facts and myths

Many people believe that IP prevents innovation from reaching poor farmers. In fact, intellectual property (IP) rights help to stimulate and share innovations.

The Syngenta Foundation for Sustainable Agriculture (SFSA) encourages and supports creative, balanced and progressive approaches to IP management that ensure continued innovation, and encourage the broad dissemination and use of beneficial technologies. The following points are intended to clarify a number of common misconceptions about IP.

Facts:

IP stimulates investment in innovation. IP provides a period of protection for innovators, which is vital to recoup their investments in R&D. For patents this is usually 20 years from patent filing and at least 20 years for PVP rights. Currently, at a time when public agricultural research funding has been declining, the top 15 plant science companies are investing about $5 billion per annum in R&D for seeds and crop protection. Without enforceable IP protection, this investment will not continue, to the detriment of agricultural development and food security the world over.

IP can catalyze public-private partnerships for humanitarian uses. Legal ownership of innovations through IP rights necessitates the liaison and agreement being reached between interested parties. In the case of public-private partnerships, this dialogue can bring unexpected synergistic benefits. These do not just involve access to technology but also particularly partnering on scientific know-how, innovation development and reach of technology to resource-poor farmers.

IP is not a limiting factor in many poor countries. To benefit from IP, inventors must apply for and be granted rights in each national sovereignty. Not all countries have IP systems in place; in some countries rights may not be enforceable. For these business and practical reasons, innovations are not always protected by patents or PVP, particularly in some of the resource-poorest countries such as in Africa. However, there are significant benefits to working with technology creators and developers. SFSA encourages researchers in developing countries to seek know-how, cooperation and support for humanitarian uses, rather than unilaterally trying tactically to avoid IP rights of technology owners.

IP supports knowledge-sharing. Patents require the disclosure of an invention in order to be granted. They therefore provide an important publication communication tool about new scientific discoveries. Intellectual property rights reward plant breeders and inventors for their creativity, and provide an incentive for developing innovative technology and products for the marketplace.

Myths:

Patents grant ownership of life. The concept of “life” cannot be patented, and no IP system confers ownership of a living organism.

Patents prevent farmers from saving seeds. The “farmer’s privilege” of saving seed is respected in international legal systems, such as the International Union for the Protection of New Varieties of Plants (UPOV). Farm-saved seeds produced by poor farmers for non-commercial use are outside the scope of IP protection.

IP prevents farmers and breeders from using known plants, seeds, or practices. No valid patent or plant variety protection right can claim a variety or resource that is already known in nature. No IP prevents a breeder or farmer from using existing plants or using established processes.

Approaches to IP management

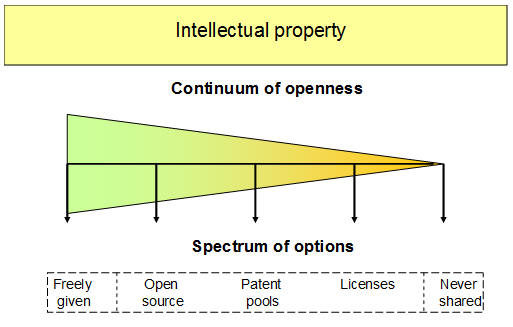

- Over the last 20 years there has been acceleration in technology creation, and in conjunction, an increasing use of IP. The complexity of patent portfolios, the competitive business environment and the need for rapid product regeneration have brought a wealth of new ideas on how to protect inventions while also accessing critical technology and know-how so vital for new product development.

- There are many possible options for protection of intellectual property and enablement of freedom to operate (FTO):

1. IP licenses

- Royalty-free license. One of the most straightforward options for enabling humanitarian use of innovations is using a royalty-free license. This allows the parties or designated researchers to use an invention freely for humanitarian purposes. This option is fine for bilateral arrangements. However, when there is a very large landscape of IP, with multiple parties and uncertainty of complete ownership, this type of approach can be very time-consuming and expensive to negotiate and administer.

- Non-assertion covenant. Here an IP owner promises not to enforce IP rights for a specified field of use in specified countries. This lowers the transaction costs, can be applied to individual or multiple parties, and, in some instances, can reduce potential for liability. It can also be useful for research-related uses in countries like the USA that have only limited research exemptions in patent laws.

2. Patent commons and licensing platforms

- This approach seeks to make patents, know-how and resources of companies and public organizations more widely available for the improvement of neglected crops. It encourages members of an otherwise competitive industry to join in a common cause with the public sector to create something that is for their collective benefit.

- Parties agree to make their intellectual property accessible though a common platform 4. The IP is accessible to all parties (whether or not they contribute IP to the platform) under commonly agreed rules. The platform can agree to grant free licenses in specific countries, such as the world’s least developed nations, and have different terms for commercialization of technology elsewhere.

- Patent commons require a robust patent base to prevent “free riding” by commercial 3rdparties, and to encourage a sustainable growth of the innovation pool. In contrast to the software area, where open source platforms are supported by copyright protections, plant related inventions require explicit protection by patents or PVP to prevent unauthorized third-party use.

4 Krattiger A. 2007. Freedom to Operate, Public Sector Research and Product-Development Partnerships: Strategies and

Risk-Management Options. In Intellectual Property Management in Health and Agricultural Innovation: A Handbook of

Best Practices (eds. A Krattiger, RT Mahoney, L Nelsen, et al.). MIHR: Oxford, U.K., and PIPRA: Davis, U.S.A. Available online at www.ipHandbook.org.

Characteristics of patent commons

| Advantages | Potential issues for management |

|

|

3. Open-source. This type of access is typical of “donation” type activities that may come with some provisions – i.e. licensees are not allowed to restrict public availability. It is unrealistic to expect the private sector to provide global open-access of proprietary technology in the plant science arena, due to liability and stewardship issues that must be managed.

Best practice and options to consider:

- IP policy and strategy. It is essential to find creative and progressive ways to enable humanitarian use while at the same time respecting the need of the private sector to protect its vital income streams. Often the different missions of the public and private sector are reflected in their approaches to IP:

- Private sector: driven by criticality of defending their freedom-to-operate and preventing “free rides” by commercial competitors in developed markets.

- Public sector: often prefers publication rather than seeking IP protection. This can be due to conflicts with internal institutional policy, or an underlying belief that IP is in conflict with the creation and dissemination of public goods.

SFSA recommends that an IP policy and strategy is always agreed for the potential fruits of the collaboration. This needs to be fit-for-purpose, pragmatic, cost-effective, operable, and to use all parties’ strengths.

- New innovation models. New, “open” and consultative innovation models are key to the continued future success of plant breeding and to address future challenges for resource-poor farmers. SFSA believes in these concepts and the use of collaborative networks, particularly for the following challenges:

- Freedom to operate. A full understanding of the IP in the field of interest is critical to prevent the R&D program from contravening any third party’s rights, and to enable the output products to be developed and reach farmers without impediment. This is particularly important for agricultural biotechnology research, where the situation can be complex with patents and plant variety protection rights at different stages of the grant process. It is essential to prevent “free riders” from blocking a PPP’s FTO, particularly in the area of seeds.

- There are two aspects to assessing FTO; it is important not to confuse them:

- Transparency. A key enabler for creation of an IP strategy in a PPP is for all parties to be transparent and explicit about their landscape of owned intellectual property and other operational contractual arrangements with third parties. Specifics of ownership of IP on a country basis need to be shared.

- Ownership. It should be expected that all parties in a PPP, and especially the private sector, will want to retain ownership of background IP. The only element for discussion will be “foreground IP”, which covers inventions created during the PPP. To enable commercialization, license rights to the background IP may need to be granted.

Shared ownership can sometimes seem a good option, but becomes problematic and difficult to manage. Co-ownership can result in higher costs, difficulties in IP management, enforcement, and tax implications. This needs careful consideration as part of an agreement.

- Inventorship. Sometimes confusion can occur when parties mistakenly believe that ownership of the IP is the same as inventorship, and that both parties should have staff as named inventors. It is critical that the importance of correct inventorship is understood, as without this patents are invalid. The relevant national legal requirements for invention conception and reduction to practice should be adopted.

- Benefit-sharing and re-negotiation. An aspect that can sometimes be overlooked and will be especially important for the public sector party is to ensure that if ground-breaking discoveries are made that lead to major commercial profits, some renegotiation of the equability of the benefits from the inventions is possible. This needs to be addressed by terms for re-negotiation.

- IP costs and management. It is recommended that the parties discuss who is best placed to operationally manage, maintain, and administer IP filings. Often this will be the private sector party. A key point that is sometimes not taken into full consideration is who will pay for filing, language translations, and maintenance of the IP. The costs can quickly mount and are tightly linked to the number of countries where protection is sought. For example: translation and filing in 10 countries can cost between $100-150K, and usually incurs additional maintenance payments of >$10k per year. Costs increase greatly as more countries are covered and can reach almost $1m total for 20 countries.

- Patent filing. To benefit from intellectual property, inventors must apply for and be granted rights in each sovereign nation. For multiple countries a coordinated application can be filed using a Patent Cooperation Treaty (PCT) in accordance with the Paris Convention for the Protection of Industrial Property. However, this application still has to be translated for, and validated and examined in each of the individual countries. In many cases, domestic market size does not justify these efforts financially. Thus the private sector does not seek IP in every country in the world.

- Competition law. Interested parties are encouraged to seek legal advice and to reflect on the guidelines published by national governments, such as the US Department of Justice (DOJ), Federal Trade Commission (FTC) and Patent and Trademark Office (PTC).

- Awareness of international legislation. In addition to specific national and international legislation on intellectual property mentioned previously, there are a number of key additional international treaties that can have a bearing on a PPP, its content, scope, and construction. The following need to be taken into consideration:

- Agreement on Trade-Related Aspects of Intellectual Property Rights (TRIPS).Comprehensive multilateral agreement on intellectual property and international trade with a broad scope. For genomic research it has increased the spread of private rights over products and processes used.

- International Convention for the Protection of New Varieties of Plants (UPOV Convention) is an internationally recognized intellectual property system for the protection of new plant varieties.

- Convention on Biological Diversity (CBD). Conservation and sustainable use of biodiversity. Covers access and equitable benefits-sharing between countries for use of wild genetic resources, and involves an advanced informed consent procedure.

- Cartagena Biosafety Protocol. To protect biological diversity and its sustainable use from the potential risks posed by living modified organisms from modern biotechnology. Specifically applies to the international movement, transit, handling, and use of all living genetically modified organisms. It involves an advance informed agreement procedure between parties before the movement of organisms.

- Kuala Lumpur-Nagoya Supplementary Protocol to Cartagena Biosafety Protocolestablishes an internationally binding claim for countries importing genetically modified organisms (GMOs) to make the responsible producer in the exporting country liable for any possible damage.

- International Treaty on Plant Genetic Resources for Food and Agriculture (PGRFA) provisions for the conservation and sustainable use of plant genetic resources for food and agriculture. Multilateral system for exchanges of plant germplasm of major crops that includes donor countries’ rights to royalty payments from commercialized products.

- International Plant Protection Convention (IPPC) is a multilateral treaty for cooperation in plant protection that aims to prevent the spread and introduction of pests and pathogens of plants and plant products between countries.

- National laws of technology and germplasm transfer. Several countries limit the transfer of technology and germplasm across their borders. Approvals by governmental authorities need to be obtained. In some cases even the agreement between the parties regulating the transfer requires approval. Careful monitoring of these obligations is necessary to avoid violations, which in some countries are seen as a severe crime.

- Creation and support for Public-Private Partnerships. SFSA is able to assist prospective PPP parties with ideas on how to ensure that IP and collaboration strategies will support humanitarian uses and technology R&D for resource-poor farmers.