“The greatest benefit is in deepening impact”

There is much talk about the benefits of ‘remote sensing’ in agriculture. But which companies and technologies could most help smallholders? Our Foundation and partners recently examined this and other questions in a study. What did it find, and where is remote sensing headed in smallholder farming? We asked John Mundy. He is the Head of Climate Finance and Technology Partnerships at One Acre Fund.

Syngenta Foundation: What, very simply, is ‘remote sensing’?

John Mundy: Tools that help us see things in farmers’ fields from high in the sky or out in space.

That sounds like the kind of hi-tech that matches large-scale commercial agriculture. Isn’t it rather ‘overkill’ for smallholder farming?

Not at all! Smallholders farm in a wide range of environments. To support them appropriately, we need to understand their individual situation. Remote sensing enables us to tailor and deploy products and services suited to local soil types, weather, etc. Those can vary significantly, even within a single region.

But at organizations such as yours, isn’t that the task of field teams?

Conventionally, yes, we would all try to identify farmers’ needs through field officer surveys. But that approach takes up a lot of time. And sometimes the information is simply too difficult to collect, because of the distances and settings in which we work. Even when our field officers have good access, they can often only visit each farmer 3 or 4 times per year. For many aspects of farming, that is too seldom to keep properly up to date.

Why did One Acre Fund decide to run this study?

Because remote sensing could play a major role in helping smallholders cope better with climate change. They are among the world’s most climate-vulnerable people. One Acre Fund is determined to build its resilience. We provide advice (for example, on suitable agronomy) and new products (e.g., insurance). Excitingly, in some cases, we can also enable smallholder access to carbon markets. The study helps identify the best remote sensing support.

Technology has been around for a while. Why did you study the offers only recently?

Because of the rapidly growing momentum around imagery and analytics. We wanted to understand the technology’s viability and the top performers for our six specific use cases. These are Agroforestry & aboveground biomass carbon monitoring, Flood detection, Soil properties (including carbon), Yield measurement, Field delineation, and Crop health.

Speaking personally, what surprised you about the study findings?

That the technologies vary so much in functionality and performance. I’d assumed that observing fields accurately from space would give strong imaging power for all our use cases. Instead, we learned that the crucial element is the process of analytics – i.e., what happens between generating the image and using the data. In some cases, like soil carbon forecasting, we rely on machine learning techniques layered over remote sensing imagery. The analytics there remains to be fully proven. There is a way to go before we can accurately and cost-efficiently predict soil carbon without taking field samples. On the other hand, we also discovered providers who are ready to support us now. Before this report, we weren’t aware of their capabilities – or sometimes even their existence!

Remote sensing helps tailor innovations to smallholders’ needs. Where do you see the greatest potential for these farmers to soon benefit more?

Remote sensing can enable multiple improvements that are highly localized and context-specific. These are in two main areas. One is field mapping, geotagging, and field delineation; the other is weather and climate. In the first area, for example, remote sensing can support local agronomy recommendations, such as for a planting date or fertilizer application. A major benefit on the climate side would be the development of more specific insurance products, without the need for weather stations.

There are still some big remote sensing gaps in the smallholder area. Which ones would One Acre Fund like to see filled first?

We need high-resolution imagery, frequently shared – and crucially, at a low cost. A gap for analytics providers to fill would be in-house support for machine learning systems, data science, and quality data management. However, remote sensing is unlikely ever to be fully automated. There is therefore also a continuing need to fund ‘ground truth’ data collection.

In other words: do people tend to exaggerate the potential of remote sensing?

Outside our sector, yes. I think there is often more hype than a real understanding of the use cases or the possible impact on smallholder products and services.

It’s critical that we don’t see remote sensing as fully automated solutions that replace ‘boots on the ground’. Our field teams and analysts often provide data that form a baseline and inform machine learning. I don’t see that stopping. In fact, as the remote sensing sector becomes more applied to smallholder settings, the hunger for ground truth data will grow. There will thus be an increasing need for field teams that are really good at collecting and managing farm-level data. Those teams also ensure a crucial aspect that remote sensing can never achieve: our personal relationship with smallholders.

What is your advice to funding organizations contemplating support for remote sensing?

Many funders seem to assume that its main advantage is reducing program costs – for instance, by saving field officers’ time. And yes, technology could make some products cheaper. But in our view, remote sensing primarily adds value by deepening impact. For smallholders, we believe its main benefit will be on the revenue side, not in cost reduction. We now need to clarify this with better field-based pilots and use cases.

There are numerous companies of various types and focus in the remote sensing market. Where are they mainly based, and how interested are they in smallholders?

That’s another important point. Most of these companies are based outside Africa. As a result, their data sets tend not to be supported by the ground truth numbers we need as training material for machine learning and analytics. The companies can provide imaging support in Africa, but my impression is that they are not very motivated to do so. In addition, the prices for smaller pixel sizes or more frequent data provision tend to be too high for African contexts.

For One Acre Fund, what were the pros and cons of partnering with our Foundation on this study?

The Syngenta Foundation has been an excellent thought partner. We are very grateful for the support, and for the help in disseminating the findings to a large audience.

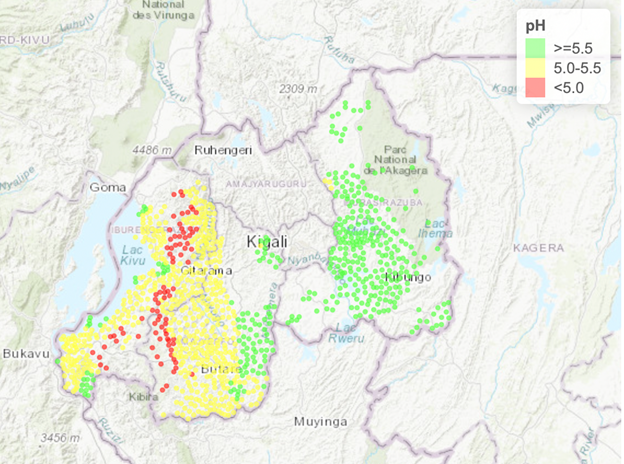

The pH data are from iSDA soil maps, One Acre Fund created this view using open street maps.

John lead’s One Acre Fund’s efforts to connect climate finance and technology to Africa’s largest networks of smallholder farmers. John is a social enterprise and international development entrepreneur with extensive technology, food security, and green economy strategy roles including strategy lead for the World Food Programme’s Farm to Market Alliance, digital climate-smart agriculture director at Mercy Corps AgriFin, field organizer President Obama’s first campaign, and a consultant with green economy pioneer Majora Carter. Earlier in his career, he founded a social enterprise in Peru manufacturing improved cookstoves linked to voluntary carbon markets. John holds an MA in Social Enterprise and a BA in International Development.